The Patterson-Gimlin Footage - New Revelations

Re-examination of the Patterson–Gimlin Film and Its Enduring Questions

The world-famous Patterson-Gimlin footage was captured in 1967 by Roger Patterson and Bob Gimlin, at Bluff Creek, near Orleans, northern California, which would become the most important footage ever captured in the field of Cryptozoology. Moreover, this is the second most analysed footage in the world, with the Zapruder film of JFK’s assassination taking the top spot.

How to support my work:

Buy My Books. Paperback, Kindle and Kindle Unlimited:

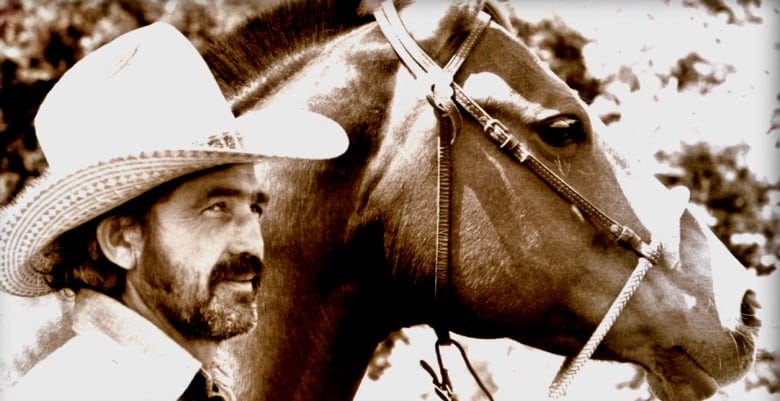

Roger Pattison

Roger Patterson was born in 1926 and grew up in the western United States, shaped by rural life and frontier traditions. As an adult, he worked as a rodeo hand and was a capable rodeo cowboy, accustomed to livestock, horses, and the sustained physical demands of such work. His experience placed him within the practical, outdoors-focused communities of the American West, where physical skill and endurance were valued more than formal education.

Patterson did not maintain a single, settled profession. Over the course of his adult life he worked as a labourer, showman, writer, and independent filmmaker, pursuing projects that reflected his interests and convictions. He possessed a persuasive personality and was able to enlist support for his ideas, though his financial situation remained unstable and he frequently relied on borrowed funds.

Not unlike myself, Patterson had become deeply engaged with reports of large, unidentified creatures in the Pacific Northwest. He read widely on Native American traditions, regional folklore, and contemporary footprint discoveries, with particular attention to Northern California. These studies led to the publication of his self-financed book Do Abominable Snowmen of America Really Exist?, in which he proposed the survival of a relic hominid species. He included drawings representing his interpretation of the creature’s appearance, images that later became central to the debate about his expectations prior to the filming.

Patterson’s interest extended beyond researching Bigfoot from afar. He identified Bluff Creek as a site associated with repeated footprint finds and eyewitness accounts and organised expeditions to the area with the explicit aim of obtaining physical or visual evidence. Central to this effort was his decision to acquire professional-grade filming equipment. Patterson rented a 16 mm motion picture camera, along with colour film stock, at a time when such equipment was costly and well beyond casual or hobby use. Renting the camera required a financial commitment he could ill afford, reinforcing that the trip was planned around documentation rather than chance observation.

He borrowed money to cover the rental, film stock, and travel costs, and timed the expedition to make full use of the limited filming window the rental allowed. The choice of a 16 mm camera stood out because it was typically used for documentaries, news footage, and commercial productions, not personal outings. The expedition of October 1967 formed part of this deliberate and sustained effort to secure visual evidence under conditions he believed offered the best opportunity for success.

Following the filming, Patterson sought to bring the footage to public and scientific attention through organised screenings and outreach. Disputes over ownership, revenue, and distribution arose, contributing to tensions with associates and further complicating his reputation. These difficulties followed him for the remainder of his life and remain part of assessments of his character.

Patterson died in 1972 at the age of 46 from Hodgkin’s lymphoma. He did not withdraw his claims about the film, and he did not present evidence of a fabricated origin. Later assertions by others regarding involvement in a hoax have not been supported by contemporary documentation or physical materials.

Patterson’s legacy is defined by contradiction and persistence. His personal reliability is debated, yet the film he produced continues to be analysed independently of his character. His life remains closely linked to the footage, though it no longer determines how the material itself is evaluated.

Bob Gimlin

Bob was born in 1931 and grew up within the rural working culture of the American West. He earned his living as a horseman, wrangler, and ranch worker, developing practical skills rooted in daily work rather than formal training. His life was shaped by long periods spent in remote terrain, where familiarity with animals, land, and environmental conditions was essential.

Gimlin stated in interviews that he had Cherokee ancestry as part of his family background, which was consistent with the oral family histories common in many western communities. It is frequently cited in accounts of his life and is often referenced in discussions of his background and skills in the outdoors.

What is well supported is Gimlin’s reputation as a capable outdoorsman and tracker. Through his work with horses and livestock, he developed an ability to read ground sign, animal movement, and disturbances in natural terrain. These skills were practical rather than theoretical, acquired through necessity and repetition. He was accustomed to identifying tracks, broken vegetation, and changes in soil that indicated recent activity, and to distinguishing between signs left by known animals and those that appeared unusual.

Gimlin met Roger Patterson through shared interests and regional connections. While aware of reports of large unidentified creatures, he did not pursue the subject independently or seek public attention for it. His involvement in the Bluff Creek expedition arose from personal association and practical usefulness rather than advocacy or ambition. He joined the trip primarily to assist with horses, navigation, and field support.

On 20 October 1967, Gimlin was present during the filming at Bluff Creek. While Patterson advanced with the camera, Gimlin remained with the horses, later stating that he observed the figure clearly as it moved across the creek bed and into the forest. He described its size, movement, and physical presence in terms consistent with someone accustomed to evaluating animals in open terrain. His account of the encounter has remained stable across decades.

After the filming, Gimlin withdrew from public involvement. He did not participate in the promotion of the footage and did not seek financial benefit from it. Disputes over film rights and revenue proceeded without his engagement, and he returned to private life, continuing work in rural occupations. For many years he avoided interviews altogether.

When Gimlin later chose to speak publicly, his statements remained restrained and consistent. He maintained that the event itself occurred as described, while refraining from speculation about the creature’s nature. He consistently denied any involvement in staging or fabrication and rejected later hoax claims attributed to others.

Gimlin’s role in the history of the footage rests on continuity rather than prominence. His account has shown little variation over time, and his life followed a path largely separate from the film’s cultural impact. While debate over the footage continues, his testimony remains one of its most stable elements.

The Location

The filming took place at Bluff Creek, a remote tributary of the Klamath River in northern California. In 1967 the area lay deep within rugged forest and logging country, characterised by steep banks, dense undergrowth, and limited access by rough tracks. The landscape was shaped by seasonal flooding, leaving wide gravel beds, exposed sandbars, and soft alluvial soil that readily preserved tracks and impressions.

Bluff Creek already held a reputation long before the filming. Throughout the late 1950s and early 1960s, the surrounding region became associated with repeated reports of unusually large footprints, many discovered by road crews and loggers working in the area. These finds were documented locally and circulated nationally, contributing to the popularisation of the term “Bigfoot”. The frequency of reports gave Bluff Creek a distinct place in the developing folklore of the Pacific Northwest.

The physical setting played a significant role in why the location drew attention. The creek bed provided clear sightlines and open ground, contrasting with the surrounding forest, while the bordering tree line offered natural cover. Tracks could be followed for considerable distances along the gravel and sand, and movement across the creek bed would be plainly visible. The area also supported abundant wildlife, including deer and elk, making the presence of large animals unremarkable in itself.

In October 1967 the site remained largely unchanged from earlier years, with no nearby settlements and minimal human traffic. Logging activity occurred intermittently, but large stretches of the creek were isolated for long periods. This combination of accessibility for expeditions and isolation from regular observation made Bluff Creek a focal point for those seeking evidence of unusual activity.

Following the filming, Bluff Creek became inseparable from the history of the footage. The location was revisited repeatedly by researchers, investigators, sceptics, and enthusiasts, each attempting to reconcile the physical environment with what appeared on film. Measurements of stride length, ground slope, and sightlines were conducted over decades, using the creek bed as a reference point for scale and movement.

Today, Bluff Creek is recognised less as a single incident site and more as a landscape layered with history. It represents the intersection of environment, folklore, and documentation, a place where geography itself became part of the ongoing debate. Regardless of interpretation, the location remains central to understanding the context in which the footage was captured and why it has endured.

Bigfoot

Across cultures and continents, accounts describe a large, hair-covered, upright being that lives at the margins of human settlement. These figures appear in folklore, oral history, and modern eyewitness testimony, often sharing consistent traits despite geographic separation. They are typically described as tall, powerfully built, bipedal, and elusive, inhabiting forests, mountains, or remote wilderness. In many traditions, they are portrayed as intelligent, cautious, and aware of human presence rather than as purely animal.

A recurring detail in these accounts is a powerful and distinctive odour associated with the creature’s presence. Witnesses frequently report a sudden, overwhelming smell described as a combination of rotting organic matter, wet animal fur, and stagnant earth. The odour often precedes visual contact, lingers briefly in the area, and then fades once the presence withdraws. This sensory detail appears in reports from multiple regions and cultures, reinforcing its place as a common element within the broader tradition.

In the Himalayan regions of Nepal, Tibet, and northern India, the being is known as the Yeti. Local accounts describe a creature adapted to high-altitude terrain, often associated with snowfields and remote mountain passes. Stories of the Yeti predate Western exploration and were part of established Sherpa and Tibetan tradition long before they entered global popular culture.

Across Central Asia and the Caucasus, similar beings are known as Almas. Descriptions emphasise a more humanlike appearance, sometimes including reports of tool use or interaction with villages. These accounts persisted through the Soviet era, during which researchers collected testimonies from rural populations who regarded the Almas as a rare but real presence.

In Southeast Asia, particularly on the island of Sumatra, reports focus on a smaller but equally elusive figure known as the Orang Pendek. Witnesses describe a compact, upright being moving swiftly through dense rainforest. Local communities often treat such encounters as part of the natural order rather than as extraordinary events.

Australia has its own longstanding tradition in the form of the Yowie. Aboriginal oral histories include references to large, hairy beings inhabiting the bush and mountain ranges. Later colonial accounts echoed these descriptions, often recording encounters in regions far from permanent settlement.

In North America, these traditions converge in what is now commonly known as Bigfoot, also referred to as Sasquatch, a name derived from Indigenous languages of the Pacific Northwest. Indigenous accounts long predate modern sightings and describe beings that occupy a space between the natural and spiritual worlds. In the twentieth century, reports expanded into broader public awareness through footprint discoveries, eyewitness encounters, and photographic and film claims.

Taken together, these global accounts form a pattern that transcends individual cultures. Whether understood as folklore, misidentified wildlife, or something not yet categorised, the persistence of these figures across continents suggests a shared human experience with the unknown edges of the natural world. North America’s Bigfoot stands as the most widely recognised name, but it represents only the latest chapter in a much older and far broader tradition.

The Bluff Creek Encounter

Roger Patterson and Bob Gimlin were in the Bluff Creek region as part of a planned expedition. Patterson had identified the area due to its history of large footprint discoveries and eyewitness reports and had organised the trip with the intention of securing physical or visual evidence. The expedition was already underway for several days, with the men travelling on horseback through logging tracks and creek beds, surveying terrain and looking for sign.

On the morning of 20 October 1967, the two were riding along the gravel bed, a shallow tributary bordered by steep banks and dense forest. The creek bed formed a natural corridor of open ground, framed by tree line and undergrowth. The weather was clear and dry, with good visibility. The time was late morning, shortly after midday by most reconstructions, with the sun high enough to cast defined shadows across the gravel.

As they rounded a bend in the creek, Patterson’s horse reacted violently. The animal spooked sharply, rearing and throwing Patterson to the ground. Both men later emphasised the intensity of the reaction. Patterson was an experienced rodeo cowboy and horseman, accustomed to unpredictable animals, and the sudden panic suggested to him that the horse had reacted to something unfamiliar and alarming in close proximity.

From the ground, Patterson saw a large, upright, hair-covered figure moving away from them on the opposite side of the creek bed, near the tree line. He immediately reached for the 16 mm camera stored in a saddlebag. The urgency of the moment meant the camera was brought into use while Patterson was still regaining balance and moving at speed. This accounts for the opening seconds of the footage, which are unstable and briefly out of focus.

The film then settles enough to capture the figure confirming its upright gait, long stride, and broad proportions. As it walks away, it turns its head and upper body toward the camera before continuing into the trees. The sequence lasts less than a minute, yet records clear movement across open ground, muscle motion beneath hair, and a distinctive walking pattern.

Gimlin remained with the horses, later stating that he had a clear, unobstructed view of the figure during the encounter. Both men described a strong sense of shock and urgency. Patterson focused on filming, while Gimlin worked to keep the animals under control. Neither attempted pursuit beyond the filming itself.

After the encounter, the men remained in the area long enough to examine the creek bed and surrounding ground, noting large footprints consistent with earlier reports from the region. Patterson was aware that he needed to return to town promptly. The rented camera and film stock represented a significant financial commitment, and the footage needed to be secured and developed as soon as possible. The urgency of preserving the film added to the pressure of the moment.

The encounter ended as abruptly as it began. What remained was a short reel of exposed film and a shared experience that both men later described as unexpected, intense, and deeply unsettling. The events of that late morning would go on to form one of the most closely examined moments in the history of unexplained phenomena.

Below is some of the footage which goes beyond what is usually shown when discussing this clip. It shows small snapshots of the location before the event, followed by the sighting.

Public Reaction

In the weeks following the filming, the story spread with unusual speed for a pre-internet era. News of the footage moved first through regional newspapers in northern California and the Pacific Northwest, where interest in large footprint discoveries was already established. From there it was picked up by wire services and syndicated outlets, allowing the story to travel nationally within days rather than months.

Public screenings of the film played a decisive role. Patterson arranged showings in theatres, halls, and lecture venues, presenting the footage directly to paying audiences. This approach placed the film in front of the public before any settled interpretation could form. Viewers encountered the images raw and unresolved, which amplified debate rather than closing it down. Each screening generated fresh local coverage, extending the story geographically as it moved from town to town.

National magazines soon followed. Still frames from the film were reproduced in widely circulated publications, introducing the image of the upright figure to millions who would never attend a screening. One particular frame, 357, later became known as the look-back frame and became iconic almost immediately. It condensed the entire event into a single, unsettling moment that could be printed, shared, and remembered.

Television further accelerated the spread. News segments and talk shows discussed the footage as part of a broader fascination with unexplained phenomena that characterised the late 1960s. The film appeared alongside stories of UFO sightings and other mysteries, situating it within a cultural moment already receptive to the unknown. This context ensured that the footage reached audiences far beyond those actively interested in folklore or wilderness reports.

The story crossed national borders quickly. Coverage appeared in Canada, Europe, and parts of Asia, often framed as an American mystery rooted in vast, remote landscapes. The image of the creature came to represent a specifically North American unknown, yet its reception was global. Few short films, particularly those shot outside institutional or scientific settings, achieved that level of international recognition.

Debate emerged almost immediately. Supporters and sceptics responded in equal measure, each new article or broadcast prompting letters, counterclaims, and further commentary. Importantly, no single explanation gained early dominance. The absence of closure allowed the story to persist rather than peak and fade, keeping the footage in circulation long after most news items would have been forgotten.

Within a year, the film had moved beyond a local curiosity and become a permanent reference point. It reshaped public perception of Bigfoot from a loosely defined folklore figure into a specific image with a recognisable form and gait. The speed and breadth of its spread ensured that the footage did not merely document an event but created a cultural touchstone that continues to frame discussion decades later.

Scrutiny and the Absence of Resolution

From its first public release, the footage was subjected to intense and sustained examination. Scientists, filmmakers, anatomists, and sceptical investigators analysed it frame by frame, measuring proportions, gait, stride length, and interaction with the terrain. Each new generation revisited the same images using improved techniques, extending scrutiny rather than resolving it.

Explanations centred on costumes, human performance, and fabrication were explored in detail. Known ape suits, materials, and methods available in the 1960s were compared against the figure’s proportions and movement. Human reconstructions using prosthetics or modified footwear were tested, but none accounted for all observed features without introducing new problems.

The credibility and motives of those involved were also examined, and claims of hoaxes or confessions appeared periodically. These assertions failed to produce physical evidence or a consistent account that explained the footage in full.

Over time, no single interpretation proved comprehensive. Each explanation addressed some aspects while leaving others unresolved. Rather than reaching closure, the footage settled into an unresolved category. The absence of a satisfactory explanation became a defining feature of the case, ensuring its continued examination decades after it was filmed.

Modern Analysis and Revelations

Advances in digital stabilisation and image processing have allowed the Patterson–Gimlin film to be examined with a level of clarity unavailable to earlier researchers. Modern stabilisation reduces camera shake and motion blur, isolating the subject’s movement and bringing previously obscured anatomical detail into focus.

One of the most notable outcomes of this analysis is the widely held interpretation that the figure appears to be female. Stabilised sequences show two distinct breasts moving independently of the torso during locomotion. The motion is pendulous and asynchronous, responding naturally to changes in stride and upper-body rotation, and remaining consistent across multiple frames.

These observations are supported by broader biomechanical features. Rotation through the shoulders and hips produces secondary motion in the chest that follows momentum and gravity in a coherent manner, persisting across several strides and camera angles.

Here is the footage upscaled and stabilised.

As this interpretation became established, the figure came to be informally known as Patty, a name derived from Roger Patterson’s surname. The term functions as a practical reference, distinguishing the filmed subject from the broader idea of Bigfoot, and is now widely used in both critical and supportive analysis.

The implications of a female subject are notable. At the time the film was shot, a female Bigfoot would likely have been viewed as less immediately believable and ran counter to prevailing expectations. From a biological perspective, the presence of a female individual suggests population continuity rather than a singular or anomalous encounter.

Modern analysis has not resolved the nature of the figure, but it has sharpened the focus of inquiry. The stabilised footage continues to yield new observations, reinforcing the film’s status as an enduring and unresolved case.

The Patterson–Gimlin film endures because it has never been resolved. Time, technology, and repeated scrutiny have refined understanding without delivering a definitive explanation. New analysis has revealed additional detail, shifted interpretations, and focused attention on the figure itself, now commonly referred to as Patty.

Neither the circumstances of its capture nor the lives of those involved point to a clear resolution. The footage remains resistant to simple classification, continuing to invite examination decades after it was filmed. Its significance lies in that persistence, an unresolved record that continues to challenge explanation.

Bigfoot Vocalisation: The Samurai Chatter

Although unrelated to the Patterson–Gimlin film, it provides additional context to include other significant Bigfoot-related experiences reported during the same general period.

The recording commonly referred to as the “Samurai Chatter” forms part of what is collectively known as the Sierra Sounds, captured in the Sierra Nevada mountains of California in 1971. The recordings were made by Ron Morehead and Al Berry, who were camping and prospecting in a remote wilderness area when they began experiencing repeated nighttime vocalisations originating from the surrounding forest.

The sounds captured consist of the banging of tree trunks and rapid, rhythmic sequences of short vocal bursts. These include clicks, pops, guttural tones, and sharp consonant-like noises delivered in quick succession. Many listeners have described the overall effect as resembling structured vocalisation or rapid conversation, which led to the informal nickname “Samurai Chatter”.

The recordings display internal structure and variation. The sounds occur in grouped sequences with shifts in pitch, tempo, and emphasis. In several segments, overlapping vocalisations are audible, suggesting more than one source operating simultaneously. Some passages convey a sense of alternation or exchange, giving the impression of interaction rather than a single continuous call.

The audio was captured using reel-to-reel tape equipment available at the time, with microphones positioned outside the shelter to minimise interference. The proximity of the sound source resulted in recordings of unusual clarity relative to many other reported vocalisations. Background elements on the tapes include movement, wood knocks, and close-range environmental noise, details that align with other reported encounter contexts.

In subsequent years, portions of the recordings were examined by linguists and sound engineers. Analyses focused on vocal range, speed, and complexity, with some assessments noting characteristics that exceeded typical parameters of known North American wildlife. The rapid transitions and layered sounds became a focal point of discussion and remain a subject of debate.

Within Bigfoot research, the Samurai Chatter is frequently cited as an example of complex vocal behaviour suggestive of intentional communication. Interpretations vary, and no consensus explanation has been reached regarding the origin of the sounds.

More than five decades after they were recorded, the 1971 Sierra Sounds remain among the most studied and replayed pieces of alleged Bigfoot audio. Their enduring significance lies in how distinctly they present vocalisation as patterned, deliberate, and closely resembling conversational exchange.

For a full explanation and analysis, this is a documentary made by a great YouTube Channel, Cabin in the Woods.

A request from me

As you may have noticed, I have started to add a lot of my research and source material into the articles, in the form of easy-to-consume images and videos. If you enjoy these or not, please let me know either way, in the comments.

Thanks for reading.

The fact no one has come forward with a credible hoax claim is important. The fact that no one has ever been able to duplicate the costume, the walk or the muscle movements lends a lot of credibility to it being authentic.

Big thumbs up from me for including the images and videos. It completes things perfectly.

I think I must've seen the original shaky footage when I was young (we're probably talking late seventies or early eighties here), and was immediately fascinated by it, so to be able to read about all this background and see the whole of the footage is really wonderful. Thank you!

As something of a feminist, I adore the idea of the creature being female! Hey-ho Patty!